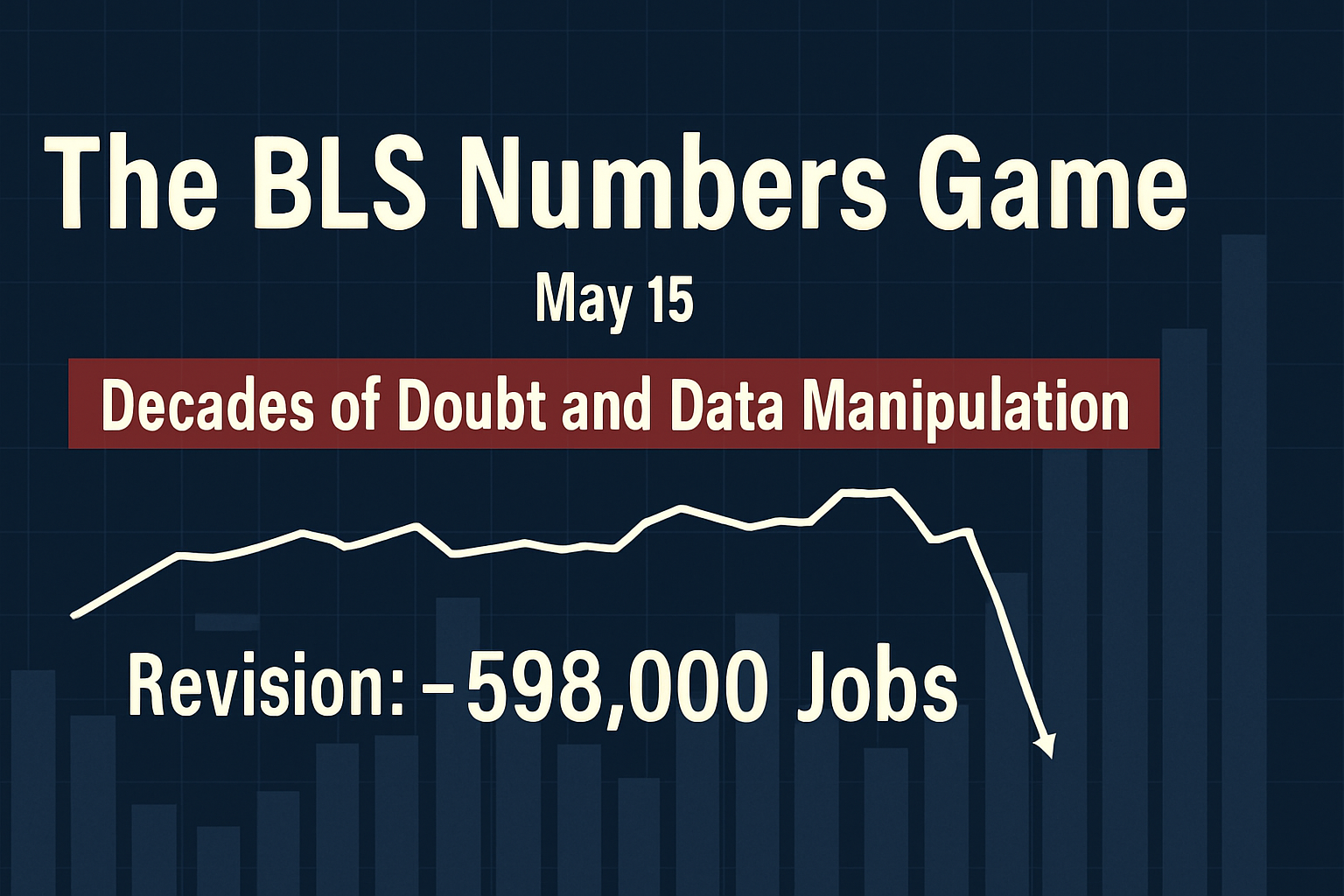

The BLS Numbers Game

Decades of Doubt and Data Manipulation

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) is often heralded as the gold standard for economic data in the United States, providing critical insights into employment, inflation, and economic health. But recent revelations, such as those highlighted in a May 2025 article from Armstrong Economics titled "BLS Data Revised – Payrolls Declined Under Biden," cast a long shadow over the agency’s credibility. According to the article, revised BLS data revealed a significant contraction in private sector payrolls under the Biden administration, with a staggering decline of 598,000 nonfarm payroll positions from March 2023 to March 2024. This revision, which contradicts earlier rosy reports, raises a critical question: Can we trust the BLS to tell the real economic story? A look back at the agency’s history and methods suggests that this is far from the first time its numbers have been called into question.

The Latest Scandal: A 598,000 Job Mirage

The Armstrong Economics piece points to a troubling pattern: the Biden administration’s initial claims of robust job growth were propped up by inflated BLS estimates, only for subsequent revisions to reveal a far bleaker reality. The BLS’s monthly nonfarm payroll estimates, based on a survey of 200,000 out of 600,000 businesses, are often touted as a snapshot of economic vitality. Yet, as the article notes, these figures are “consistently revised with somewhat minimal deviation” under normal circumstances. Under Biden, however, the revisions have been anything but minimal. The Business Employment Dynamics (BED) census, which surveys a massive 12 million businesses quarterly, exposed a decline in payrolls that obliterated earlier narratives of economic strength.

This isn’t just a one-off error. The article also highlights scandals under BLS Commissioner Erika McEntarfer, appointed by Biden in January 2024. From leaking the April CPI report to private sector economists to delaying the release of the annual nonfarm payroll revision (which was then leaked on social media), the BLS’s recent track record suggests either incompetence or deliberate obfuscation. These incidents fuel skepticism about whether the agency is serving the public or protecting political interests.

A Long History of Questionable Methods

To understand why the BLS’s credibility is under fire, we need to rewind several decades and examine its methodologies—methods that have often been criticized for masking economic realities. The BLS has a history of tweaking its formulas and definitions to present a more favorable picture, particularly during politically sensitive times. Let’s explore some of the key tactics that have raised eyebrows over the years.

The Birth/Death Model: Creating Jobs Out of Thin Air

One of the BLS’s most controversial tools is the Birth/Death Model, introduced in the early 2000s. This statistical adjustment estimates the net number of jobs created or lost due to business openings and closings that the BLS’s surveys might miss. While the concept sounds reasonable, critics argue it’s prone to overestimating job creation, especially during economic downturns. For example, during the 2008 financial crisis, the Birth/Death Model added hundreds of thousands of jobs to payroll reports, even as the economy hemorrhaged jobs. In 2009, the model was criticized for assuming business formations were robust when small businesses were collapsing en masse.

The Armstrong Economics article implicitly points to this issue by highlighting the discrepancy between the BLS’s monthly estimates and the BED census. The smaller sample size of the monthly survey, combined with adjustments like the Birth/Death Model, can create an illusion of growth that only unravels when more comprehensive data emerges. This isn’t a new trick—it’s a decades-old playbook.

Redefining Unemployment: The U-3 vs. U-6 Debate

Another way the BLS has historically softened economic realities is through its definition of unemployment. The headline unemployment rate, known as U-3, counts only those actively seeking work and excludes discouraged workers, those marginally attached to the labor force, and part-time workers who want full-time jobs. The broader U-6 measure, which includes these groups, often paints a much grimmer picture but rarely makes the headlines.

This practice dates back to the 1990s, when the BLS refined its unemployment metrics under the Clinton administration. The shift to emphasizing U-3 allowed policymakers to tout lower unemployment rates, even when underemployment and discouraged workers were significant issues. For instance, during the early 2000s recovery, U-3 hovered around 5-6%, while U-6 was closer to 10-12%. By focusing on the narrower metric, the BLS helped create a narrative of economic strength that didn’t fully align with workers’ experiences.

The recent payroll revisions under Biden echo this tactic. By initially reporting robust job growth, the BLS bolstered the administration’s claims of economic success, only for the BED census to reveal a contraction. This selective reporting mirrors the U-3/U-6 sleight of hand, prioritizing optics over reality.

Hedonic Adjustments and Inflation: Downplaying Rising Costs

While the Armstrong Economics article focuses on payrolls, the BLS’s questionable methods extend to other areas, like inflation. The Consumer Price Index (CPI), another BLS product, has long been criticized for understating the true cost-of-living increases Americans face. One key culprit is “hedonic adjustments,” introduced in the 1980s, which account for quality improvements in goods and services. For example, if a new laptop costs the same as last year’s model but has better features, the BLS might record a price decrease, even if consumers are still paying the same amount.

This methodology, championed during the Reagan era, helped lower reported inflation rates, making economic conditions appear more stable. However, it often disconnects CPI from the lived experiences of households grappling with rising costs for essentials like housing, healthcare, and education. The 2025 CPI leak scandal mentioned in the Armstrong Economics article suggests that even today, the BLS’s inflation data may be subject to manipulation or premature dissemination to favored insiders.

Seasonal Adjustments: Smoothing Out the Truth

The BLS’s use of seasonal adjustments is another long-standing practice that can obscure economic trends. These adjustments aim to account for predictable fluctuations, like holiday hiring or summer slowdowns. But critics argue they can be overly aggressive, flattening out real economic volatility to create a smoother narrative. During the 1970s stagflation era, for instance, seasonal adjustments were accused of understating job losses in industries like manufacturing, which were hit hard by economic shifts.

The 598,000-job revision highlighted in the Armstrong Economics article suggests that seasonal adjustments, combined with the Birth/Death Model, may have inflated initial payroll estimates under Biden. When the BED census provided a clearer picture, the adjustments couldn’t hide the decline.

Political Pressures and Institutional Bias

Beyond methodology, the BLS’s susceptibility to political influence is a recurring concern. Commissioners like Erika McEntarfer are political appointees, and their leadership can shape how data is presented or prioritized. The Armstrong Economics article notes McEntarfer’s tenure has been marred by leaks and delays, raising questions about whether the BLS is being steered to serve administrative goals rather than public transparency.

This isn’t a new phenomenon. In the 1980s, under Reagan, the BLS faced accusations of downplaying unemployment to support deregulation policies. In the 1990s, Clinton’s administration was criticized for leveraging BLS data to exaggerate the benefits of NAFTA. The 2008 financial crisis saw similar debates, with Obama-era reports accused of using optimistic assumptions to signal a quicker recovery. Each administration has an incentive to present the economy in the best light, and the BLS, despite its reputation for independence, operates within this political ecosystem.

What’s at Stake?

The stakes of BLS’s credibility crisis are enormous. As the Armstrong Economics article underscores, economic data drives “trillions of dollars in decisions—from interest rates to pensions.” Misleading payroll numbers can distort monetary policy, mislead investors, and erode public trust. If the private sector contracted by 598,000 jobs under Biden, as the BED census suggests, then earlier claims of economic resilience were not just inaccurate—they were potentially deceptive. This isn’t just about one administration; it’s about an agency whose methods have long been questioned for obscuring the truth.

For the average American, these revisions translate to real-world consequences. Inflated job numbers can delay policy interventions, like stimulus or tax relief, that might address economic hardship. Meanwhile, the gap between headline figures and lived realities—like stagnant wages or underemployment—fuels distrust in institutions. When the BLS’s initial reports are consistently revised downward, as they were under Biden, it’s hard to see the agency as a neutral arbiter of truth.